McKinsey conducted a global survey of more than 1,000 directors and found that “boards with better dynamics and processes, as well as those that execute core activities more effectively, report stronger financial performance at the companies they serve.” This shows how important an effective board is to a business and why you should invest in your board of directors’ development.

The more your board develops, the better equipped it is to face the challenges of a fast-moving business landscape. The way directors tackle the challenges and emerging compliance issues is key to gaining that competitive edge over your peers.

Furthermore, Karen Brice, director of governance and board advisory at Grant Thornton remarks “executive and non-executive directors alike tell us that, if their board isn’t adapting fast enough to provide the kind of leadership that is needed to protect and grow the organisation, they could face an increasing sense of isolation from management teams.”

WHAT IS BOARD DEVELOPMENT?

Board development is the process of helping your directors gain access to resources that enable them to improve their individual and collective performance and effectiveness. This could be:

Sharing best practices

Undertaking specific training for continual improvement

Filling skills gaps

Increasing board diversity

Regular evaluations to assess progress

Having a defined role to focus on

Providing access to relevant papers and reports

The benefits of regular director training

There are a number of benefits of undertaking regular director training, for everyone from CEOs to new board members. These include:

Helping forge bonds

Corporate boards do not have the time to forge close bonds if the only time they interact is during meetings. Bringing them together out of the business environment allows them to network in a less formal space where they can be more relaxed and get to know each other better.

This connection can only help in future meetings, making miscommunication less likely, as directors understand each other more deeply. It aids collaboration and facilitates more productive discussion because the members who disagree are less likely to do so with hostility and will be more inclined to find an amicable solution.

Futureproofing the organisation

The business world is growing and changing all the time, with new capabilities, possibilities and risks entering our consciousness. Regular training helps you avoid treading water and keeps you competitive by ensuring you are on top of new technology and current best practices. Besides, it helps you navigate potential corporate minefields in the short, medium and long term.

Training arms your directors with the tools they need to take advantage of the governance landscape and making it a regular activity means that they are always aware of recent developments and predictions.

Encouraging better decision making

Training gives board members better clarity when it comes to early recognition of problems and difficulties for the business. This allows discussions to take place early, in a less pressured manner, giving the board breathing space to fully debate and develop a solution that works.

Without this ability, the board might not recognise a critical threat until it becomes an urgent issue, meaning that there is a tight deadline on decision-making and less time for reasoned, insightful discussion.

7 steps to better director development

1. Evaluate the current composition

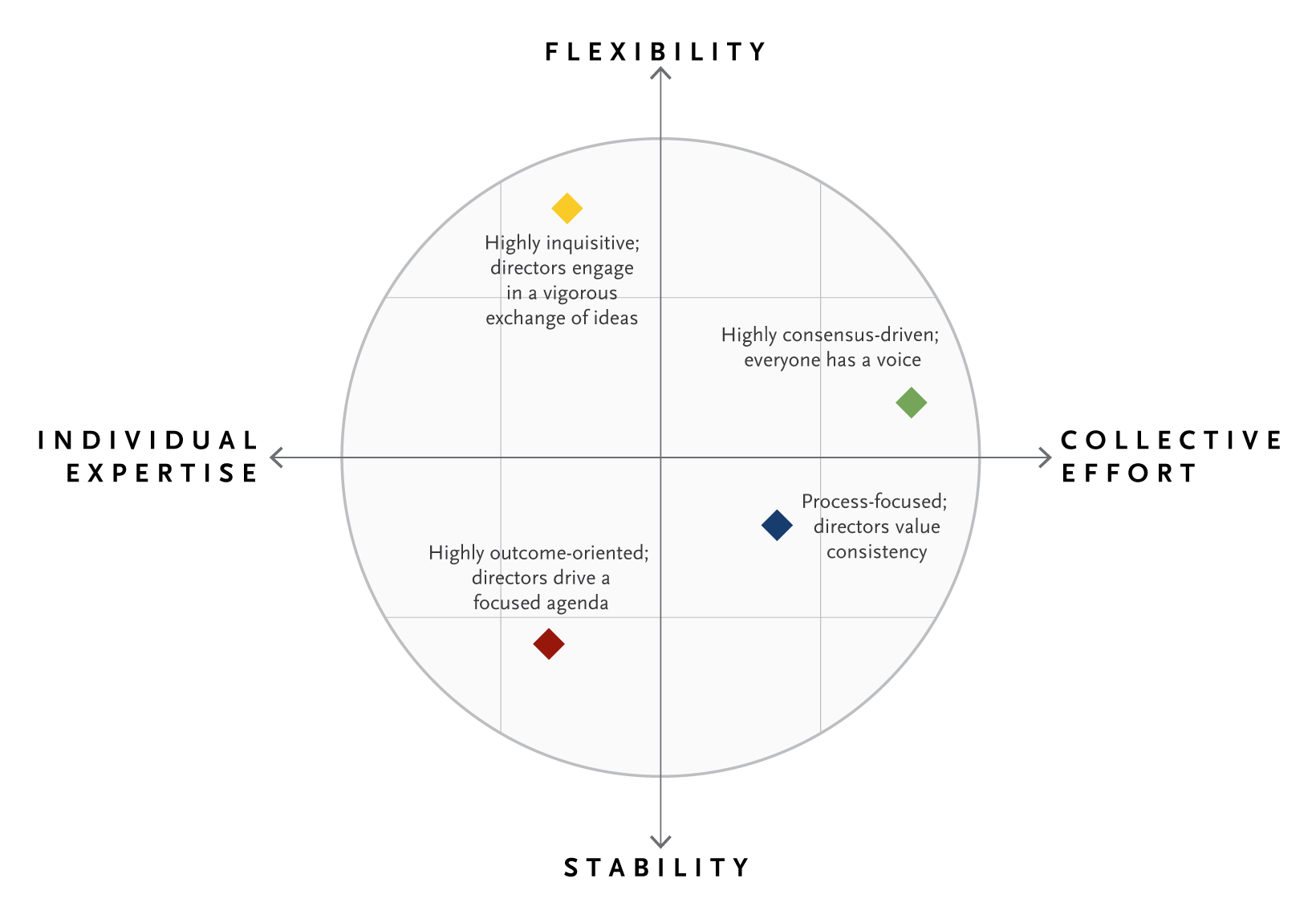

The composition of the board is vital in director development, as it dictates the array of competencies and experiences, as well as attitudes, that make up the board. Understanding your current board composition allows you to decide what training would benefit the individuals and, therefore, the collective. This will form the basis of your recruitment strategy.

Here are some elements that you should consider:

—————

2. Revise board structure

Based on the discussions you have about composition, you can expand to look at the structure of the board as a whole. How can it be improved to facilitate a better flow of information and decision-making?

Is the structure working well right now? If so, consider if this will be the case in the future and consider what changes are needed to keep it fresh and effective.

3. Write down role descriptions

Almost every job that someone applies for has an extensive role description, detailing exactly what the company will expect of the successful candidate. It makes sense that the board of directors works in the same manner. When new directors are recruited to the board, they are there for a reason and not just to make up the numbers around the boardroom table.

Each director should understand what is expected of them so that they can focus on how best they can contribute to the success of the organisation’s strategy. Writing down detailed role descriptions for directors is essential for development as it guides them down specific paths and allows them to think more strategically.

4. Conduct a skills audit

Once you have role descriptions, you can audit the skills possessed by your current board and analyse how they can be developed in order to fulfil those role responsibilities.

If a director is expected to understand the market in-depth, but they have only basic knowledge of the industry, this is a skill that you need to develop through training or recruitment.

Personal development training is one way to address this skills gap. In addition, you could organise team training sessions or boot camps.

5. Set a clear vision

In order to further hone your audit, you need to understand where you want to go. This dictates the skills you need to achieve your aims. Having a clear vision of the board contributes in the same way that writing specific role descriptions does.

It provides goals for directors to work to and a way of measuring progress. If you can benchmark where you are and understand where you want to go, it is easier to see what needs to change to help you achieve your strategic goals.

6. Carry out annual reviews

Board evaluations are essential to ensuring directors are successfully working towards the collective vision. By understanding what you have or haven’t achieved in the preceding 12 months, you can shape the direction of work for the next year in a manner that will increase effectiveness.

An annual board review looks into the work of the board individually and as a collective, uncovering skills gaps, collating feedback, clarifying objectives and much more. Using Boardclic’s Board Evaluation tool, you can utilise this benchmark data to understand what success actually looks like in your sector and to give you a competitive edge over your peers.

7. Organise refresher training every year

Induction is one thing but regular training should also be a part of your director development programme. It is also important to refresh directors’ existing competencies every year. This helps to foster a culture of continuous improvement, which encourages board members to keep striving to greater heights.

The best performing boards do not rest on their laurels but spend time reflecting on their skill sets, improving and expanding them.

FAQ

How can you encourage directors to attend training?

Encourage individual board members to attend a training programme by giving them control over the training they undertake. Rather than booking training sessions and then fitting your directors into the slots, hold a discussion with the board where you encourage members to suggest types of training that they would like to attend, within the areas in which you would like to see development.

Ensuring the style of training fits the schedule of the individual director also helps. Some board members just do not have the time to spare to attend a three-day boot camp workshop. They would probably benefit more from bite-sized sessions instead.

Do you need a board development committee?

You do not have to have a board development committee, but it does make the process of identifying training opportunities, organising activity and tracking success much easier.

When it functions properly, it contributes to a diverse and well-rounded board that is best equipped to tackle the challenges and embrace the opportunities thrown at it. These committee meetings can help provide executive teams with specific guidance on how to best equip themselves to fulfil the responsibilities of the board.

How to measure board development success?

The success of your executive board development is borne out in the effectiveness of the board overall. You can measure this using Boardclic’s board evaluation platform. It can track your progress in each specific area against both your own benchmark and that of the industry in which you operate.

Conclusion

There is no option to stand still in the corporate world, and that certainly applies to board of directors development. Growing skill sets and expertise as well as consistently seeking out best practices and emerging risk factors are both essential to being able to compete, increase resilience and steer an organisation along the right path.

An important element of board development is your annual board evaluation. It can help you discover skills gaps, pinpoint critical challenges and create an open and transparent, collaborative environment.

Source: boardclic.com